HWHF Funded Scientist, Michael Beck, and Colleague Discuss Economic Impact of Mangroves

Originally published by The Conversation. Original article available here.

Protecting Mangroves Can Protect Billions of Dollars in Global Flooding Damage Each Year

Authors: Michael Beck, Pelayo Menendez

March 10, 2020

Hurricanes and tropical storms are estimated to cost the U.S. economy more than US$50 billion yearly in damage from winds and flooding. And as these storms travel across the Atlantic, they also ravage many Caribbean nations.

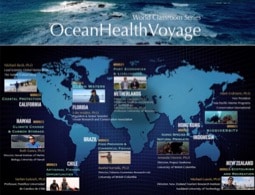

We study coastal ecosystems and how to value the natural coastal defenses provided by mangroves, marshes and coral reefs. In a new study, we map flood risks along more than 435,000 miles (700,000 kilometers) of subtropical shoreline in 59 countries around the world.

Along these coasts, we calculate that flood risks exceed $730 billion annually in direct impacts to property. Many government agencies and insurers estimate that indirect impacts to livelihoods and other economic activity are two to three times these direct flood costs.

We also estimate that across these 59 countries, mangroves – salt-tolerant trees that grow along tropical coastlines worldwide – reduce risk to more than 15 million people and prevent more than $65 billion in property damages every year. Mangroves do this by blocking storm surge– the rise in sea level during storms – and dampening waves, which protect people and structures near the shore.

Battered coastlines

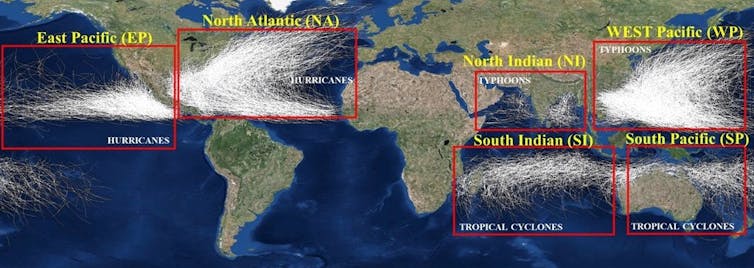

Tropical storms are a well-recognized hazard along many coasts. In 2019, which was an above-normal year for tropical storm activity, 90 named storms formed around the world, including 62 days with major tropical cyclones.

As one example, Hurricane Dorian devastated the northern Bahamas with sustained winds of some 185 miles per hour. Throughout its life, Dorian’s path impacted more than 17 nations and 15 U.S. states and territories, from Grenada to Newfoundland.

And Dorian was not even the strongest cyclone of the year. That title went to Super Typhoon Halong in the Western Pacific, which steered clear of land. Many scientists predict that climate change will make these storms more intense, with a likely increase in the proportion of storms that reach Categories 4 and 5.

It would be logical to assume that countries map the flood risks from these storms, since they have to protect residents who live near coasts, along with public infrastructure such as ports, airports, wastewater treatment centers and power plants. These facilities often are built in low-lying areas around urban and suburban centers.

However, governments and businesses only develop flood risk analyses for the shorelines of highly developed nations, where people have the resources to pay for or insure against these risks. This excludes most tropical countries, where many of the world’s most vulnerable people live.

Defending shorelines

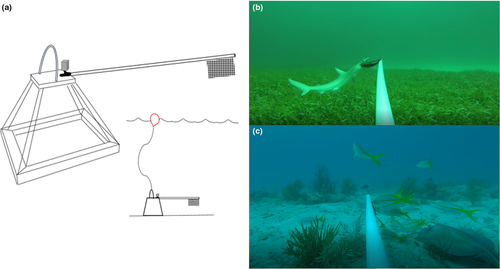

Our study was designed to quantify these flood risks worldwide and identify solutions for reducing them. We used tools that are standard in the insurance and engineering industries, along with a five-step approach for calculating expected damage, to develop high-resolution estimates of flood risk globally. Then we coupled spatially explicit hydrodynamic flood models with economics to estimate impacts to people and property.

We focused on mangroves because they are large trees that grow quickly in salt water at the edge of the coastal zone, where they form a front line of defense. Mangroves are also excellent at trapping sediments and building land. On average, land around mangroves grows vertically by 1 to 10 millimeters per year.

We generated maps summarizing the benefits that mangroves provide in 20-kilometer coastal units around the world. They show that there are 100 coastal areas where mangroves avert $100 million or more in property damages every year. These are clearly priority zones where mangrove conservation and restoration will yield highly cost-effective benefits to people, property and national budgets.

According to our estimates, the U.S., China and Taiwan receive the greatest economic benefits – protection of property – from mangroves. Vietnam, India and Bangladesh receive the greatest social benefits – protection of people.

Mangroves as green infrastructure

Mangrove destruction has been widespread, largely because of coastal development and aquaculture. From 1980 through the early 2000s, the world lost up to 20% of existing mangrove habitat. The rate of loss has slowed but still continues, driven by urban expansion, pollution and agriculture.

Given our findings about how valuable mangroves are for coastal protection, we believe they should be viewed as national infrastructure and made eligible for funding from hazard mitigation and disaster recovery budgets, just like other coastal defense structures. Paying for mangrove restoration can work through the same approaches that are currently used to fund engineered protective structures such as seawalls.

Several new studies done collaboratively with Risk Management Solutions, a leading insurance risk modeling firm, show that coastal marshes and mangroves provide significant storm reduction benefits. These findings could underpin the development of innovative insurance options for natural systems.

Examples are already being developed for coral reefs in Mexicoand across the Caribbean. Conserving mangroves where they occur together with coral reefs can multiply the flood protection benefits from habitats.

Working with the World Bank, countries like the Philippines and Jamaica are assessing how the benefits of mangroves can be incorporated into national finances, disaster management and proposals for the U.N. Green Climate Fund, which was created in 2010 to help developing countries mitigate greenhouse gas emissions and adapt to climate change. Our work was supported by the World Bank and Germany’s International Climate Initiative to help inform solutions for nations that are most at risk.

In many places, preserving and restoring mangrove forests can be an extremely economically effective strategy for protecting coasts from tropical storm damage. As national governments and insurers grapple with disaster management costs that are growing nearly exponentially worldwide, we believe our research can create new opportunities to pay for mangrove conservation and restoration using climate adaptation, disaster risk reduction and insurance funds.